ADU 535 Shirley St

Building an ADU (Grand Rapids, MI)

The first part of this article is a narrative in response to the surprising number of questions I received regarding “Why?”. Anyone interested only in the process and numbers can scroll straight down to “The Granny Flat Alternative”.

NOTE 2024-12-26: The Grand Rapids zoning ordinance has changed significantly since 2018. Special Land Use (SLU) as mentioned in this post is no longer required for ADU construction; ADUs are BY-RIGHT through-out the city. See "Zoning: Accessory Dwelling Units" for information on the current ordinances related to ADUs.

Backstory

I purchased this property in 1996 from my maternal grand father, who had purchased it from his father. My grand father needed to move into an assisted living facility and his condition-of-cooperation was that someone in the family buy the home. Never mind that the home had been neglected for decades, and sat in a neighborhood many city officials had forgotten existed [true story]. But my family had something of a tradition of keeping real-estate in the family and I was the only adult at the time who was not an “owner”. Ownership was something for which I had no aspiration – ownership is hard work. At the time however I had an extremely creepy landlord and the notion of not being monitored was appealing. So I just went along with it.

The coop

The property had an existing “garage” [which is an “Accessory Structure” in Zoning-Speak]. This structure originally served as my great grandfather’s chicken and rabbit coop. My great grandfather and his son, my grandfather, also lived in the coop as they completed the house.

The era of raising rabbits and chickens passed and someone added an overhead garage door. Yet the role as a garage for parking was inhibited as an automobile would barely fit inside; exiting a modern vehicle required crawling out through a rolled down window.

By ~2000, when this building was approaching ninety years old, the coop was gross. With a moldering roof under three layers of shingles and no proper foundation it was perpetually wet. Graciously, the city never issued me a citation for the condition of this building. I always attributed this generosity to the fact my ‘garage’ represented the majority condition of garages on the block; nobody wants to go there and start that fight.

In my first two decades of owning the property my approach was to ignore the back end of the lot – including the coop - to the greatest extent possible. The house represented an all consuming task in and of itself.

The condition of the home was bad enough that shortly after purchasing the property I received a letter warning me that if I did not find a new insurer that I risked foreclosure. The private sector insurance company I had arraigned when getting the mortgage had subsequently decided the house was too much of a risk and pulled out. That meant switching to the State of Michigan’s public property insurance option at a dramatically higher cost. Such is housing in Grand Rapids, MI where ~30,000 of the city’s stand-alone homes were constructed before 1939.

The Big Red Barn

On a property 25 minutes north of the city my family had The Big Red Barn. In its original form this building held my fraternal grandfather’s shop and accumulated tools. He had been a mechanic for the railroad and then the highway construction companies. The Big Red Barn got progressively larger as years passed. Eventually The Big Red Barn wasn’t only a barn it became the family’s venue. It was the place where one had birthday, anniversary, and retirement parties. Over the years it had been insulated, a furnace added, then a bathroom, then a kitchen.

The Big Red Barn was beloved - and it was the legacy of an era of union wages, inexpensive materials, and cheap energy; built in a place where building inspections were principally viewed as cutting into the township guy’s golf game [true story, don’t-ask-don’t-tell as a land use policy].

The Car

In the Big Red Barn lived the family’s 1919 Model-T Ford Depot Hack. This car served as a focal point for innumerable hours of collective tinkering and maintenance, it made the trek to various parades, and as far as Beaver Island. It was also regularly used to maintain the property in keeping with the family’s moral of northern pragmatism: a thing is not “preserved” if it can no longer serve its purpose.

The car winds its way through my family’s history. After Model-T’s were no longer driven as day-to-day vehicles the engine was used to power a small saw mill near Lake City which my family operated. Mounted on a skid the engine logged countless hours powering various machinery via great belts - which terrified me as a child [and as an adult I think: “rightly so”]. Using the old engine mounted on a skid rather than the power take-off hub of a tractor left the tractor available for other uses.

Change

My fraternal grand father, the principal keeper of The Big Red Barn, passed away in 2000 (1915 – 2000).

Then my father in 2012 (1939 – 2012).

Their passing severed the lingering tethers to post-war prosperity. In the context of 21st century economics the Big Red Barn and it’s property were unsustainable. All the younger members of the family, including myself, had previously retreated back to “the city”.

My mother sold the Red Barn’s property in 2015 and returned to Grand Rapids. The car was partially disassembled in order to fit into basements, and my grand father’s tools were dispersed into corners of the city.

When one’s tribe has been privileged to have a place like The Big Red Barn that place is missed when it is gone. So what to do? At minimum the car needed a new home. And what to do with all those tools and parts?

Encountering The Housing Market

My mother was 76 years old at the time she moved back to the city and had no interest in owning another home. It fell to me to find an appropriate home and to rent it back to her at cost. At that time [2015] the American “Housing Crisis” was still young and I was able to purchase a 2 bedroom home only six blocks from where she had grown up for $80K. Finding this home was a deep dive into the supply of available housing. Revealed by that experience was the reality that the great majority of homes available in Grand Rapids, MI below ~$125K are garbage. The norm at that price point is some collection of sloping floors, old roofs, wet basements, crumbling joists, and daylight shining in around the power outlets. And I won’t even mention the kitchens, which no citizen should use to prepare meals.

In addition to intimidating renovation costs nearly all the homes I toured presented accessibility issues for elderly persons, or anyone with mobility challenges. Homes had steep stair cases, narrow doorways, and all manner of trip hazards. Outdoor stairs are particularly concerning for elderly persons in Michigan due to ice. I was very fortunate to eventually have found a home which had only one low step – something which is extremely rare in Grand Rapids.

I won that round in the housing market. But the quality of the available housing, and subsequently watching the relentless price increases, left me uneasy about my ability to win if there were to be a second round. And my family is graying just as the rest of America.

A Garage?

The obvious answer to replacing The Big Red Barn and providing somewhere for The Car to live: build a garage.

In most cities the size of a “garage” [aka: Accessory Structure] is limited by the size of the lot. This is true for Grand Rapids, MI. Grand Rapids would allow a monstrous 832sq/ft garage [5.2.08.G.1] on our 5,816sq/ft lot. That is roughly speaking a four stall garage. I would have been allowed to build that “by-right”, meaning that plans would not require any special review or approval process. At that size the structure would have stretched the entire width of the rear lot, minus five foot setbacks, and been 22ft deep (36ft x 22 ft = 792sq/ft), 14ft tall.

Aside: it is 792sq/ft rather than the maximum 832sq/ft as even dimensions are more affordable. The cuts from available lengths means odd sized structures consume more material and consequently cost more per square foot. Ecologically, producing as small a pile of debris as possible is also preferable.

This straight-forward idea, which was the initial plan, had two issues.

The first issue was cost. Building a garage is not much different than building any building; it is expensive. Building a garage which would be comfortably useful year round, in Michigan, further balloons the cost. An insulated building with both heat and electrical service could easily exceed $50K. And it would add nowhere near that value to the property; from a strictly economic perspective it doesn’t make sense.

My neighborhood of Highland Park, Grand Rapids is a great place to live. It is minutes from downtown by reasonably frequent transit. It is a fifteen minute walk to the river. Yet, it remains not “cool”, and for reasons I have never understood looked down upon as “sketchy”. A home selling for more than $200K in Highland Park is rare – thus investing $50K-$60K in a garage is hard to swallow. This I assume explains the poor condition of the garages and other accessory structures in the neighborhood.

| Bedrooms | Bathrooms | Sq/Ft | Sale Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 1,375 | $145K |

| 3 | 1 | 1,127 | $160K |

| 3 | 1 | 1,050 | $140K |

| 2 | 1 | 632 | $140K |

| 3 | 1 | 1,673 | $160K |

| 3 | 1 | 1,095 | $150K |

| 3 | 1 | 971 | $145K |

The second objection to the garage was irrational; it felt wrong. A long low structure stretched across the rear of the property... picturing it in my mind such a building felt suburban. Long four stall garages belong perched on an angle next to a McMansion, itself set back from a highway by a couple acres of pointless lawn in which no child would ever be allowed to play.

I was entitled by the city ordinance to build such a garage if I wanted to. Yet it is hard to spend that kind of money on something which raises misgivings, however irrational. I have a second story deck on the rear of my house - so whatever I built – I would be doomed to spend many hours, beverage in one hand, staring at it.

There is irony I must confess on this point. I am the very first person in the room to roll my eyes at the mention of “neighborhood character” in community discussions. I despise those two words. And here I was dissuading myself from a straight-forward solution because I did not like how the building felt in my mind’s eye.

The Granny Flat Alternative

What about a “Garage Plus”?

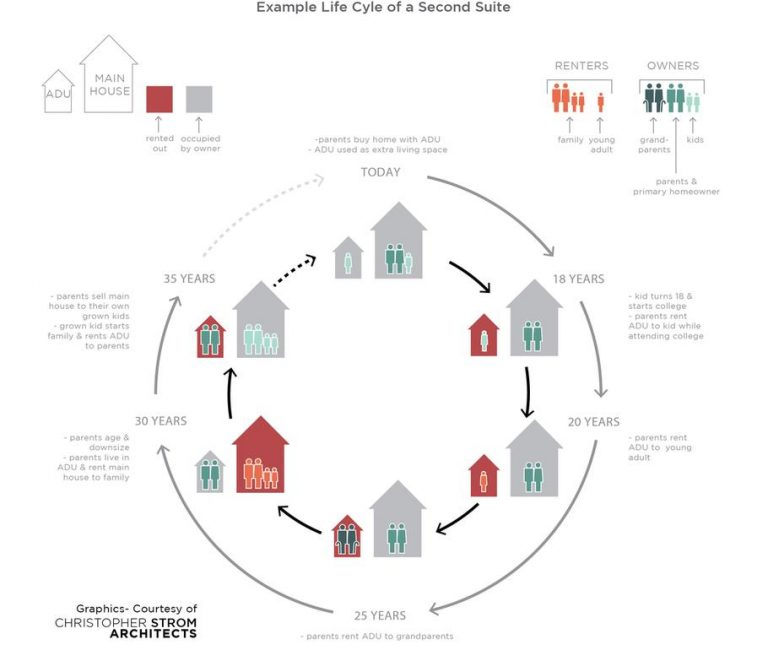

A Granny Flat is the classic ADU (Accessory Dwelling Unit) of an apartment over a garage. So called a Granny Flat due to its once having been a common housing solution for multi-generational families, before it became the cultural norm to ignore mortality and aging.

Aside: sometimes they are also called “Fonzi Flats” as the character Fonzi from the television show “Happy Days” (1974 – 1984) lived in an ADU/Granny Flat.

The advantages of the Granny Flat Alternative were numerous:

- Much of the $50K-$60K required to build a dry insulated building is redundant with building a two story residence. It feels less gratuitous when it is in support of something other than a building-sized-box for middle-class stuff.

- Housing! It could go without saying, but in a rental market where $850/mo is the floor, it needs to be said.

- When a ADU is licensed for rental the residential portion can be depreciated over 27.5 years. If I ever sell the property the depreciated amount can be deducted from any gain above a threshold. Given the low property values in Highland Park this is unlikely to amount to anything significant, but it is nice to have in the pocket if the market changes dramatically [because that never happens to the housing market . . . ]

Initial spit-ball estimates, working with my general contractor, was that an ADU is ~3x the cost of building a garage. Given that an ADU is twice the building – it has two floors – this did not strike me as unreasonable. Using this spit-ball estimate the choice was between a ~$60K garage or a ~$180-200K garage + apartment. By my reckoning that was a ~$60K garage, which would be mine, with an attached $120-140K rentable apartment. The math makes it is an easy choice.

Not to spoil the story, but that spit-ball estimate was not far off.

Aside: the lowest "affordable unit" construction cost in Grand Rapids is ~$250K. That’s 44% - 52% more than the cost of the "D" [Dwelling] in the ADU. The renovation of a vacant school building down the hill from my home into affordable housing will cost ~$14.5M for 50 units; which is ~$290K/unit. This is why cities which are serious about their "housing crisis" are plowing the regulatory road for ADUs.

Research

I was fortunate in that I knew something about American cities going in; without being armored by this foreknowledge many people who are interested in building an ADU become discouraged and abandon the idea. That truth is that American’s fear everything. American “land use” [Zoning] regulations are tedious and complicated to the point of farce. With rare exception your city does not want you to build an ADU. Thus step one to taking the ADU idea seriously is research; asking the question “What, if anything, is possible?”

What one needs first is a copy of the "Zoning" code, which is probably available online. Once this is found search (Ctrl+F!) for “Accessory Dwelling”. Hopefully you’ll find something. Reading the Zoning code is frustrating, but with a little effort one will develop a knack for it quickly enough.

A key to understanding "Zoning" is that it divides a city up into zones and then applies rules to what can be done, or built, in each zone. Usually there is a map. Find which zone your property is in and then try to cross reference the rules with your zone. My zone was “TN/LDR” where the first part, the “TN” describes with the age of the neighborhood – TraditioNal, early 1900s – while the second part “LDR” describes the preferred use: Low Density Residential [aka: single family homes]. Everywhere does its zones a bit differently.

The most unclear concept in reading a Zoning code is what is a guideline and what is a hard-and-fast rule; somethings are flexible with the correct permission and other things are not. How flexible are the flexible things? A serious cost - or what is a serious cost to non-developer normal people - is almost always attached to asking the question. That cost in Grand Rapids was $2,015 – the cost of asking for a Special Land Use (SLU) permit.

Fortunately, your city’s Planning Department is your friend. I started summarizing the zoning related to ADUs for Grand Rapids and then sent off a list of questions to the Planning Department’s contact-us e-mail. I promptly got back a detailed, informative, and honest response. In speaking to many others who have built - or attempted to build - ADUs in other cities this experience is very much the norm. Those in the Urban Planning profession embody the best finding-a-way-to-yes spirit of civil service one could hope for. It is important to do your own homework, but don’t be shy about contacting your city’s planning department.

When I described that response as “honest” what I meant was that there was text in the code which wasn’t clear and there was not much precedent on how to interpret it. One line from one of the first e-mail responses from the Planning Department: “I'm not aware of this having happened in GR, though.” The ADU related section of Grand Rapid’s code was essentially unused. So, someone had to go first.

Aside: I have talked to neighbors who have had negative experiences with my city's planning department. They felt dismissed or condescended to. The best advice I have is try again; possibly by a different method. If you called try e-mail or stopping by their office. Also try to slim your communications to strictly questions. In my experience and that of others they really do want to be helpful.

I was fortunate that at the time, vagueness aside, Grand Rapid’s regulations regarding the physical structure for an ADU were minimal, and mostly in one of those flexible sections. Unfortunately this is no longer the case, as of December 2018. It is more challenging now.

The parameters in the code, at the time, regarding the physical structure were rather straight-forward:

- Height: 25ft (two stories). For comparison the height limit of houses on my block is 35ft.

- Size: Limited to 25% the Gross Floor Area (GFA) of the house. Importantly, the GFA includes any part of the basement where the ceiling is at least 7ft high. This limitation could be waived by the planning commission.

- Building style and roof pitch must match that of the house.

- One off street parking space; not waivable.

- Other aspects fell under the same rules as a garage. Things like 40% of the lot must remain “green space”. None of these were problematic.

Aside: As more people look into building ADUs some cities are developing more readable presentations of the local code, like this one for Santa Cruz county - one of the best ones I have seen. An index of known ADU guideline documents is available @ https://accessorydwellings.org/adu-regulations-by-city/ If you find a guide not listed, or write one yourself, be sure to notify that website so they can add it to their collection.

Design

Armed with knowledge of the local regulation the next step is to sketch out the size and location of the building. This phase of the design doesn’t need to be terribly detailed, but addressing size, location on the parcel, and access are necessary to determine first if it possible, secondly to produce a better cost estimate. And lastly to have a plan with which to approach city officials. The city is not all that interested in the interior of the building, that can be left until later.

An often overlooked cost in ADU construction is site preparation. There are likely older buildings, such as my chicken coop, that will be need to be removed. Also trees, fences, etc… A first phase design is necessary to create the site preparation task list.

Size

The Gross Floor Area (GFA) of my home, including most of the basement, is 2,245sq/ft. It is important to measure this yourself and document your calculations as the GFA can be significantly different than the residential floor area, which is what you see on sites like Zillow. Residential floor area does not include basements. Also public records may be out of date or simply wrong. The residential square footage of my home, depending on the public documents I looked at, is either 1,330sq/ft or 1,568sq/ft. Measuring the first and second floor I couldn’t come up with either of those numbers.

In the end, under that “25% the gross floor area of the house” rule I could build an ADU up to ~561 sq/ft without needing to ask for the flexing of the unquantifiably flexible rules.

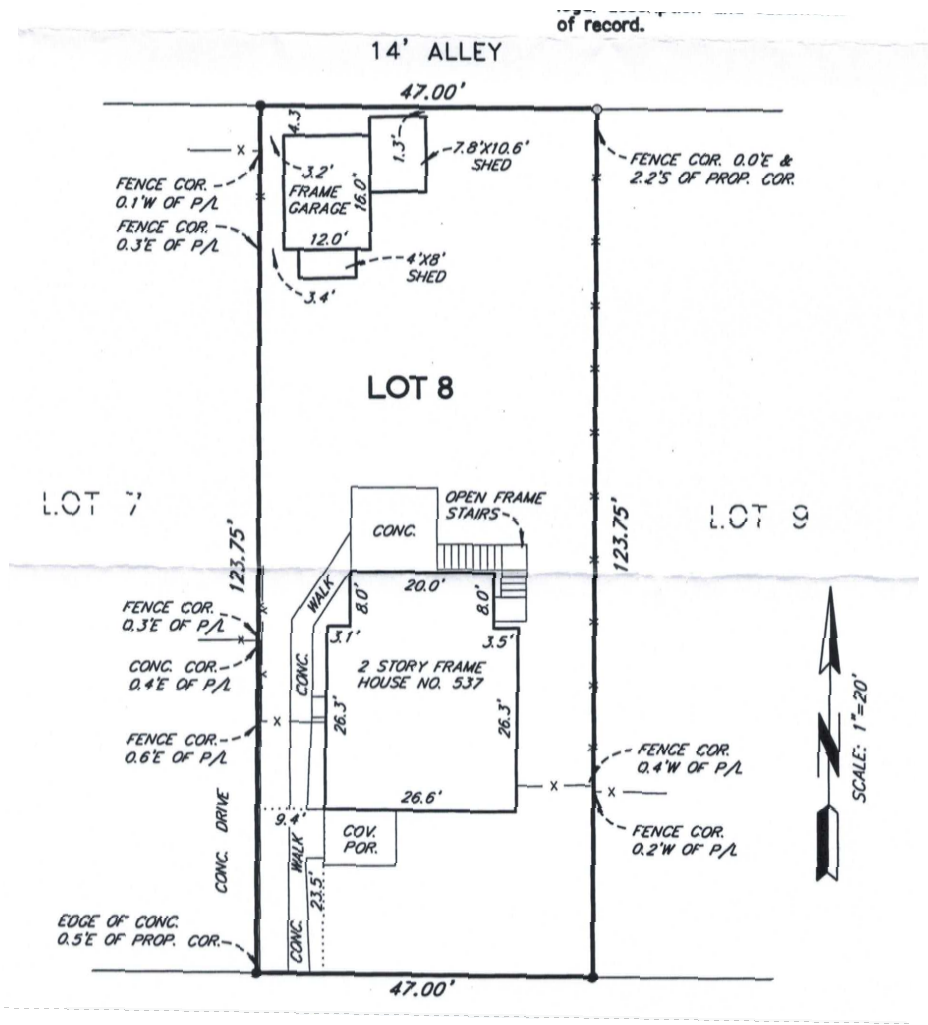

One key to getting those accurate numbers is to have a current survey. Also, any general contractor is certain to require it.

In older neighborhoods the property lines become approximated over time as people put up fences, landscape, add driveways, etc… It was not surprising that what is built on my property sits at a very slight angle. One neighbors fence wanders away from the property line as it moves toward the back of the property while the other neighbor's driveway runs over the property line at the front.

Cost of survey: $800

Parking

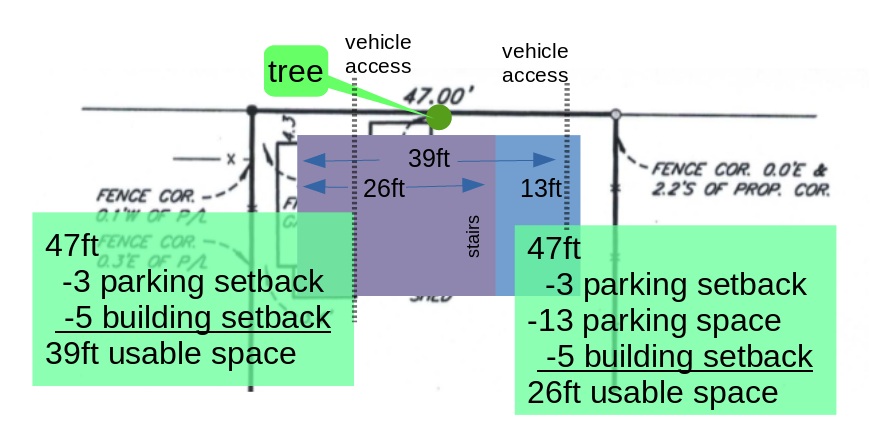

The ADU would require one parking space, and the size of a parking space is 13ftx20ft. Additionally every home in Grand Rapids is required to have two parking spaces. I began with zero parking spaces; we have always used on-street parking and had no intention of changing. Three parking spaces on the site was impossible – that requires 36x20 sq/ft = 720sq/ft, which exceeded the maximum size for an ADU structure by 28%. Add in the width of a stairway to reach the second floor and the width required exceeded the useful width of the lot by 4ft.

Fortunately, and strangely, the parking required for a home [but not the ADU] fell into the random collection of requirements that could be waived. Meaning I had my first ask: waive one parking space from the house; I’d still add one to the zero I had in relation to the house and the one required by the ADU, for two parking spaces.

The one space added in relation to the house would be the garage itself, where the Model-T Ford would live.

Location

Once I knew the actual boundaries of the lot and roughly the size of the structure the next question was to determine the location on the lot. A city’s zoning establishes “setbacks” - how far everything has to be from the property line. Fire ordinances and building codes may also specify setbacks. Any competent general contractor will know what those rules are. For my project the requirement was to be three feet from the rear of the property and five feet from the sides for any building, and three feet from the sides for a hard surface like a parking space.

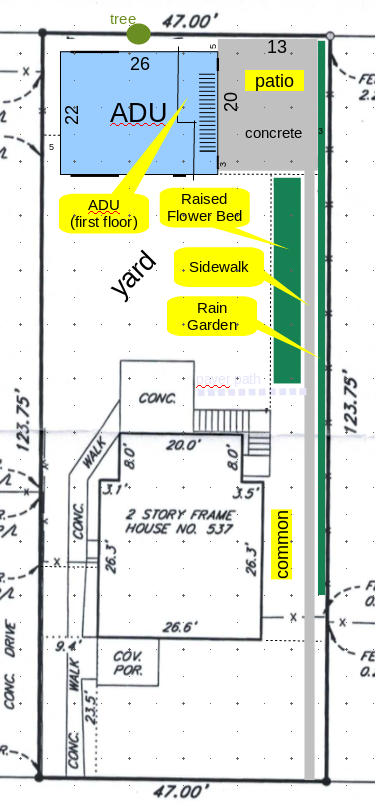

Side to side there was 37ft to work with, or 26ft including an exterior parking space. To count as a parking space [13ftx20ft] the minimum dept of the building was 20ft. The ADU’s parking space would have to be outside the structure, two parking spaces would not fit inside the structure. This put me at the 26ft number.

Notice how parking requirements dictate everything else?

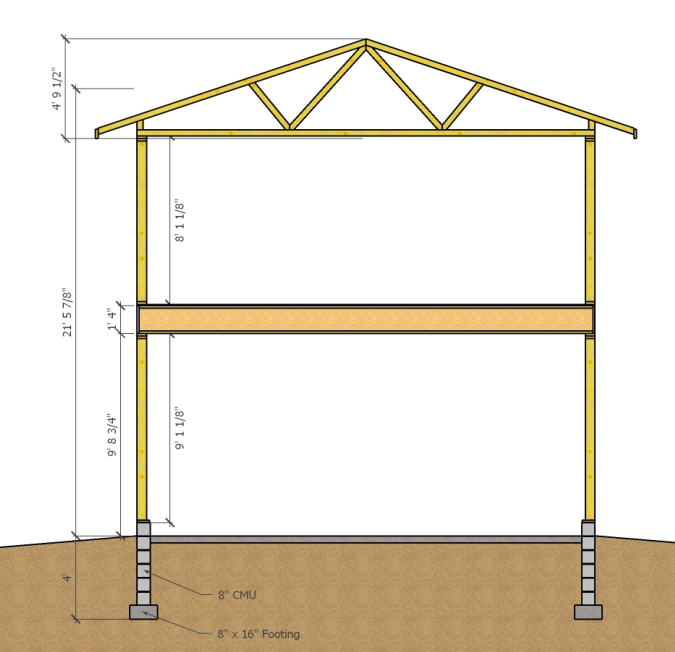

The next challenge, obvious in hindsight but unexpected, was the stairway. The placement of a stairway in a small two story structure severely limits the design. A stairway and its landings, to reach the second story over a garage, is 22ft in length. There is not anyway around that number. Given that access to the garage was from the north and the south the stairway had to be oriented north-south, giving the depth of the building a hard minimum of 22ft. Having a maximum size of 561sq/ft that depth dictated a width of 24ft – a nearly square building. A square building would have worked, but much like the long one story garage the mock-ups felt wrong. A square two story building with garage doors looked like something the power company or railroad would have on the back corner of their properties – it felt industrial. Ultimately, after many attempts to design the awkwardness out of 24x22 I decided I had to make a second ask: +2% (11sq/ft), in order to get to 26x22. It was only a change from a ratio of 12:11 to 13:11, yet – at least on a computer screen – it felt notably less square.

Aside: some of the better Zoning Codes exempt the square footage occupied by the stairway from being counted as the square footage of the ADU. Due to the smaller size of these structures such provisions are extremely helpful. The minimum square footage of the stairway is 22x3, or 66sq/ft; the stairway is 11% of the footprint of my ADU.

Access

Once the footprint and position is known the next consideration is access. The access for the parking space was straight-forward due the alley.

It was important to me that as someone’s residence it also clearly interface with the street. However “Accessory” the Zoning wanted the building to be it would be someone's home. Someone looking for the address should easily be able to find it.

I have canvassed for political candidates, ballot proposals, and mileages. That experience has made me sensitive to insular residential structures such as apartment blocks which by their design limit their occupants interaction with the surrounding community.

Complicating access is our backyard being fenced to allow the dogs the freedom to be outside without constant observation. Asking a future resident to traverse a dog occupied yard felt unreasonable.

Along the east side of the house was a narrow area which I had long ignored and was difficult to deal with due to being very wet whenever there was more than a mild rain. Previously my grand father had the area filled with ferns and other vegetation which enjoyed the dankness.

Re-purposing that dank area as a second, separated, access to the rear of the property solved multiple problems. A 4ft sidewalk there would look like an extension of the city sidewalk and feel inviting to someone visiting the ADU. It could also be fenced off from the yard creating an area that might be useful to a resident who had a pet of their own.

A 3ft x 90ft (180sq/ft) rain garden constructed along the east border of the property in the mandated 3ft setback could help with the areas moisture problem; also helping to keep that water out of the basement on the house.

I viewed the parking pad of the ADU more as a patio than a parking space; on-street parking is abundant in the neighborhood. That made me very much want to try to position the ADU opposite of where we ended up, with the patio on the west – the evening sun side – of the structure. But the various constraints made that unworkable.

I viewed the parking pad of the ADU more as a patio than a parking space; on-street parking is abundant in the neighborhood. That made me very much want to try to position the ADU opposite of where we ended up, with the patio on the west – the evening sun side – of the structure. But the various constraints made that unworkable.

In studies of ADUs the availability of private outdoor space is one of the primary reasons people choose to live them. Attention to the usability of the outdoor space shouldn’t be neglected. Subsequently we have planted a tree in the north east corner of the yard area which obstructs the view of the patio area from the main house, improving the sense of privacy.

With Granny Flat type ADUs there is a question regarding access to the garage: will the garage be available to residents of the ADU, the house, or both? In my case, as the dimensions dictated that the garage was only a single parking space, intended to be the home of the Model-T Ford, the garage would be solely related to the house.

Still, access to the ADU must begin on the ground level. Also a tenant is legally entitled to access to their utilities. My solution was to add a second exterior door into a utility room and storage area located partially under that long stairwell. This kept the utilities out of the residential space – where they would consume precious sq/ft – as well as providing the tenant with ~100sq/ft of ground level storage; a perfect place to park a bicycle, etc...

Once upon a time I was touring a facility of a “tiny home” enthusiast and all the entirely legitimate economic and ecological benefits of compact urban living where being extolled; as well as how we have moved on from being an “ownership oriented” society. During this sermonizing a young woman leaned over and quietly said to me: “all his shit is in my basement”. The motto of the story: don’t overlook the storage. People own stuff – bicycles, musical instruments, kyacks, tools - and owning stuff in an urban context should not require the monthly expense of a storage unit or squatting on a friend’s square footage. Think about storage of those larger awkward objects when thinking about access.

Lines of Sight

If you live in an older neighborhood you probably have a window that stares into the next house. It is awkward how little thought the builders put into window placement. Now with a two story ADU I was dropping more windows down into the center of the block.

My house has a second story deck on the rear which is accessed via the door of my home office. The most most obvious window arraignment meant aligning the landlord’s [me!] office with the tenants bedroom window - that’s creepy. At the same time it was that south facing wall of the ADU which would receive natural light during all seasons.

I saw a solution in a photograph: transom widows. These allow light in but still limit visibility if they are placed high in the wall. An ecological advantage appeared with that arraignment: situated up near the eave of the roof they fall into the shadow of the eave during the summer months when the sun rides high, but remain fully exposed during the cooler half of the year when the sun runs just above the roof line the house.

It was fortunate that the houses on the block are somewhat staggered between the north and south sides of the block; any accessory structure would naturally not line-up with the building on the other side of the alley. Using online maps is an easy way to look at how buildings are arraigned on a block.

The zoning of some cities has specific requirements related to window placement; others, including Traverse City, MI, have a provision allowing the City to have oversight over window placement in ADUs. The text in the Traverse City ordinance is: "be placed in a manner that provides thoughtful consideration of landscaping, screening and window placement to protect the privacy of neighbors". Grand Rapids, MI has no text relating to window placement or lines of sight. But this is as critical to good ADU design and I feel the Traverse City text does a good job of encapsulating that concern in a flexible way. Other cities, Santa Cruz, CA, for example limit windows and doors to the interior of the lot or facing the alley which is less flexible.

Height

An elevation diagram will document the project’s compliance with the height requirement. The height is measured not to the top of the structure but to the midpoint of the peak. The height limit when I constructed my ADU was 25ft, but Grand Rapids has subsequently reduced that to 20ft – while still requiring the roof pitch to match that of the primary structure [the house].

Green Space

There is a requirement that all lots in my LD [low density] zone remain 40% green space; a requirement that applies to a majority of the city. Having a ~5,700sq/ft lot this limitation did not present a challenge.

Building Style

The zoning code stated that the building’s style, roof, and materials had to match that of house. Alcoa aluminum siding – no longer available - was installed on the house sometime in the previous generation; many of the homes on the block have the same siding from the same time. I was told that modern vinyl siding of a nearly matching color was sufficiently "matching".

One deviation from the match, to which no one from the city ever objected, was the use of a textured concrete block wall between the resident’s two doors. I had both a practical and an aesthetic reason for the wall.

The practical reason is that a concrete block wall will take much more of a beating than vinyl siding, especially against things like car doors. Also, being impervious to heat, the resident could put a grill against the wall between the two doors without any issues. Vinyl siding and grills do not mix well.

The second reason is that while vinyl siding looks OK from a distance up close it looks like something made out of plastic. The neighbors fence which is the opposite border of residents patio area was wood, and a textured concrete wall kept the feeling of being surrounded by natural surfaces.

Cost of Block Wall: $1,430

I also chose to have garage doors on both sides of the garage, opening into both the alley and the yard. The garage door into the yard facilitates the use of the garage as a social space, an extension of the yard. It also allows us to move larger objects into and out of the yard which was previously not possible.

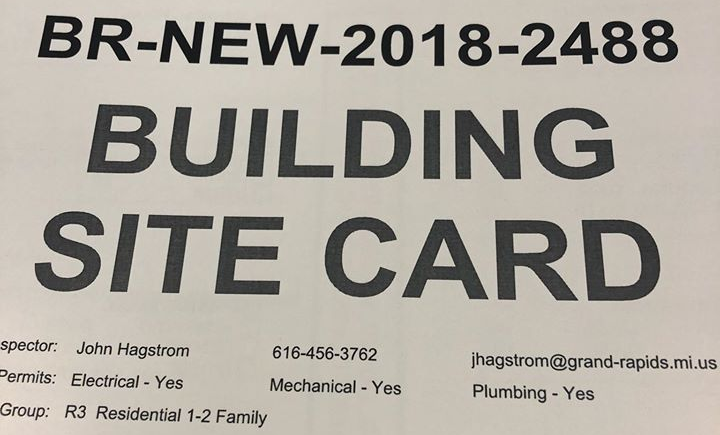

Permitting Process

Construction of an ADU in Grand Rapids required a Special Land Use (SLU) permit which is a document requested from the Planning Commission for a fee of $2,015 and then granted or denied at a public meeting. A pile of paperwork is required with the application; however almost everything required should have already been developed in the previous Design Phase #1. While the application can seem intimidating - it is eight pages – very little of it applies to a development as small as an ADU; most questions can be answered in a single sentence.

It is part of the Planning Commission’s public hearing where the asks are granted or denied in addition to the SLU overall. As a reminder the asks were:

- Exceed allowed floor space by 2% (11sq/ft)

- Reduce the parking requirement of the house form two spaces to one, allowing one of the two spaces to count for the ADU’s required parking space which could not be waived.

Outreach

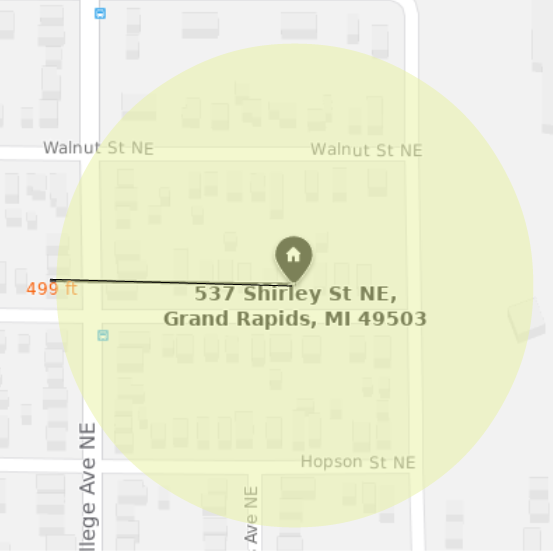

There is a requirement in the Special Land Use process to perform “neighborhood outreach”. When an SLU is applied for the Planning Department will send out a notice to all the properties within ~500ft of the site. What this radius means is easy to determine using any of the online map sites. The Neighborhood Association, if any, will also be aware the request. The best advice is to be in front of these requirements. Reach out to people in the area prior to the postcard appearing in their mailbox. Go directly to your neighbors in person – especially if you have a Neighborhood Association – own your narrative. Otherwise someone, or your Neighborhood Association, will write it for you.

For me this meant attempting to visit 57 addresses. As I have experience canvassing this did not feel challenging yet I know some people find the idea of door knocking very intimidating. Take my word for it that (a) most of the people won’t be home even if you make three attempts at different times and (b) the great majority of people you’ll meet will be curious and open minded. You’ll probably find one or two angry cranks; they make great stories for later.

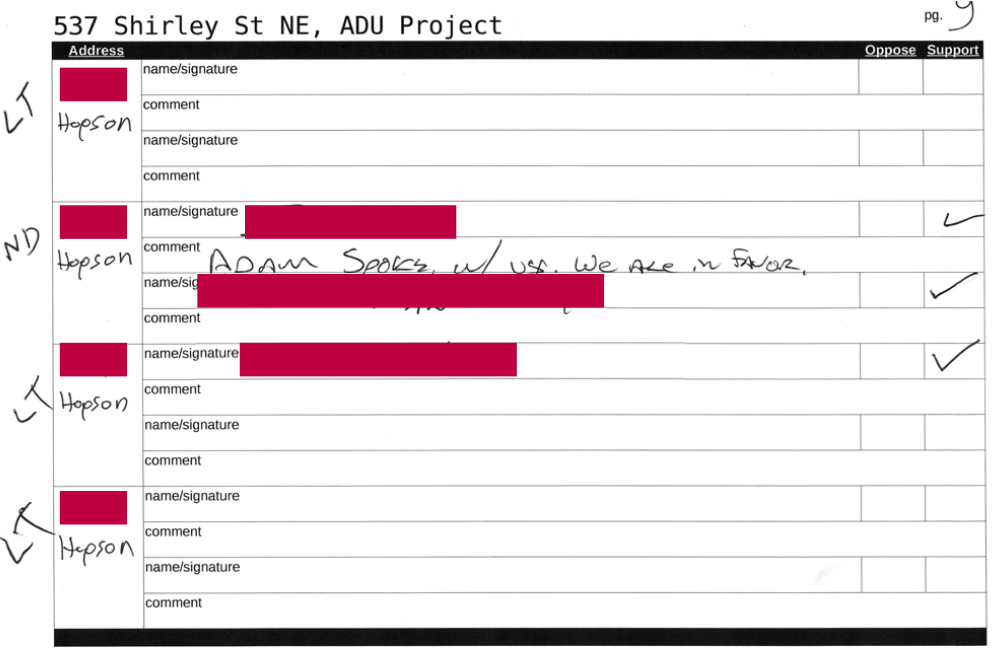

I created a signature sheet with a space for each address, so it also doubled as my checklist. Also a nice letter and some pictures. People like pictures. If no one answered the door on my third attempt at an address I left the letter behind [marked as LT on the form].

I also used the NextDoor website to send messages to the addresses if the household was registered on that platform [marked ND on the form]. It was surprising; several addresses where no one was home reached out to me, asking me to come around again so they could sign the sheet.

As time consuming as this requirement was - and as expensive as the permit application is relative to building a small structure where one already existed - the feedback from neighbors was cathartic. My favorite was the neighbor who took my clipboard with the comment “they require this to build a two story building?” as he looked up and down the street lined with two story buildings. I dissuaded him from putting expletives in the comment, as warranted as they may be.

In the end I was able to talk to 19 people, of which 11 were specifically supportive. No one chose to express opposition. Two of the 57 addresses were clearly vacant.

For full disclosure, as a fourth generation resident of the neighborhood I probably had a head start on neighbors being supportive. I had at least casually encountered many of those neighbors before. I am also a white male and English is my first language. The Special Land Use process does raise very serious equity questions; the same process for some would likely raise more opposition. Additionally Highland Park, my neighborhood, had no Neighborhood Association at the time to foment resistance to the project.

As a final tip on going door-to-door as a man: carry a few tools in your back pocket, a small wrench and a pair of screwdrivers. You are likely to be asked to help with some minor repair, particularly by older neighbors. Having experienced this previously I was prepared. In the course of my door knocking tour I helped with a loose connection to a car battery.

The Hearing

The Special Land Use permit required appearing at a public hearing before the city’s Planning Commission. These hearings take place during business hours, so having a 9-5 job required taking time off from work [another expense]. I was the third item on the agenda after an office building and another ADU.

The hearing of the project, both ADU projects, bordered on jovial – following the long tedium of the sadly suburban office building which preceded us. All the asks were granted and we were good to go!

All the documents from the Planning Commission hearing are available @ http://grandrapidscitymi.iqm2.com/Citizens/Detail_LegiFile.aspx?Frame=&MeetingID=4659&MediaPosition=&ID=6871

Site Preparation

Conversations with those who have built ADUs revealed that the cost of site preparation is often overlooked and underestimated. There is the cost of removing any existing structures – like my old chicken coop – as well as removing or limbing trees.

Trees

On the rear property line were two original shag-bark hickory trees; one dead and one of questionable health. Having recently lost many of the older trees on the block my family had a strong desire to save the still living tree. An inspection by an arborist determined that the trunk of the living tree was still sound and gave the tree a 50/50 chance of surviving the construction project. The building would be built only several feet from its base.

To improve the chances of survival we contracted with the tree service company to perform annual injections. I had no idea that tree injections were a thing.

Cost of tree removal: $2,230

Cost of tree injections: $235/yr (this will continue for five years)

Demolition

Next was the removal and disposal of the old chicken coop. The roof had begun to collapse, and with those three layers of shingles it was heavy. For safety reason I paid to have the roof of the structure removed and disposed of.

Coop Roof Removal Cost: $920

I took the task of demolishing the rest of the structure myself. Even in such an advanced state of decay breaking down ~100 year old construction is challenging; my great grandfather did not fool around when building this little structure. It’s resilience was both impressive and frustrating. In order to prevent drafts that might have disturbed the feathered and furry residents much of the building had metal sheeting under the siding.

I got lucky one day and a friend who was visiting from Texas decided to complete the demolition while I was at work.

Dumpster cost to remove debris: $560

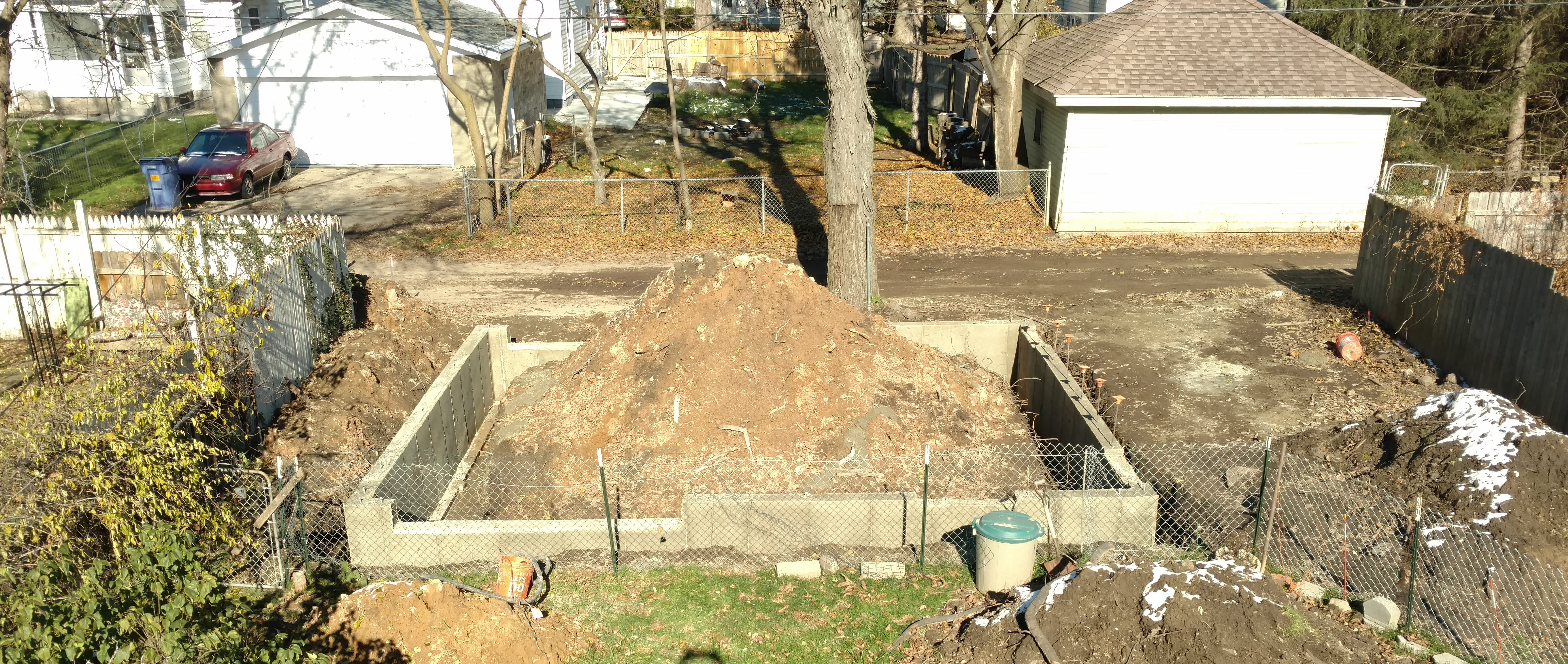

Excavation

Whenever one digs a hole in an old urban neighborhood - you never know what you are going to find.

I grew up hearing an urban legend that there had been a spring just north of the block. Given the steady flow of water onto a nearby street (Cedar St) from below the apartments which sit against the hillside I assumed there was some truth to the story. And I found more evidence. Excavation required a pump to keep the water level down.

I find the water issue ironic as I live at the top of Highland Park. You'd think we'd be dry.

There was also more debris to be removed than expected - there was the remains of the foundation of some other building under the foundation of the coop. I visited the city archives out of curiosity and could not find any records... not even of my family’s purchase of the property. The Sandborn maps have a large blank area surrounding the property. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Cost of excavation: $6,143

The lesson learned is to estimate high on site clearing and excavation costs. Maybe you’ll be lucky, but surprises are common.

Underground

All the stuff that runs underground is expensive. Also be prepared to have your yard destroyed; it is an opportunity to refresh your landscaping.

Water & Sewer Cost: $20,920

Water service for the unit must be run to the street. At the time it was arguable if the sewer could be tied into the sewer of the house or if it also had to be run to street. I chose to skip that - yet another discussion [time!] - and simply go to the street.

The City of Grand Rapids requites a Deed Restriction – cost $90 – be filed with the county preventing the ADU and the house from being divided. This voids concerns expressed in other municipal requirements and state building codes regarding one structure depending on the other for utilities. Yet... ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Underground Gas Line: $1,900

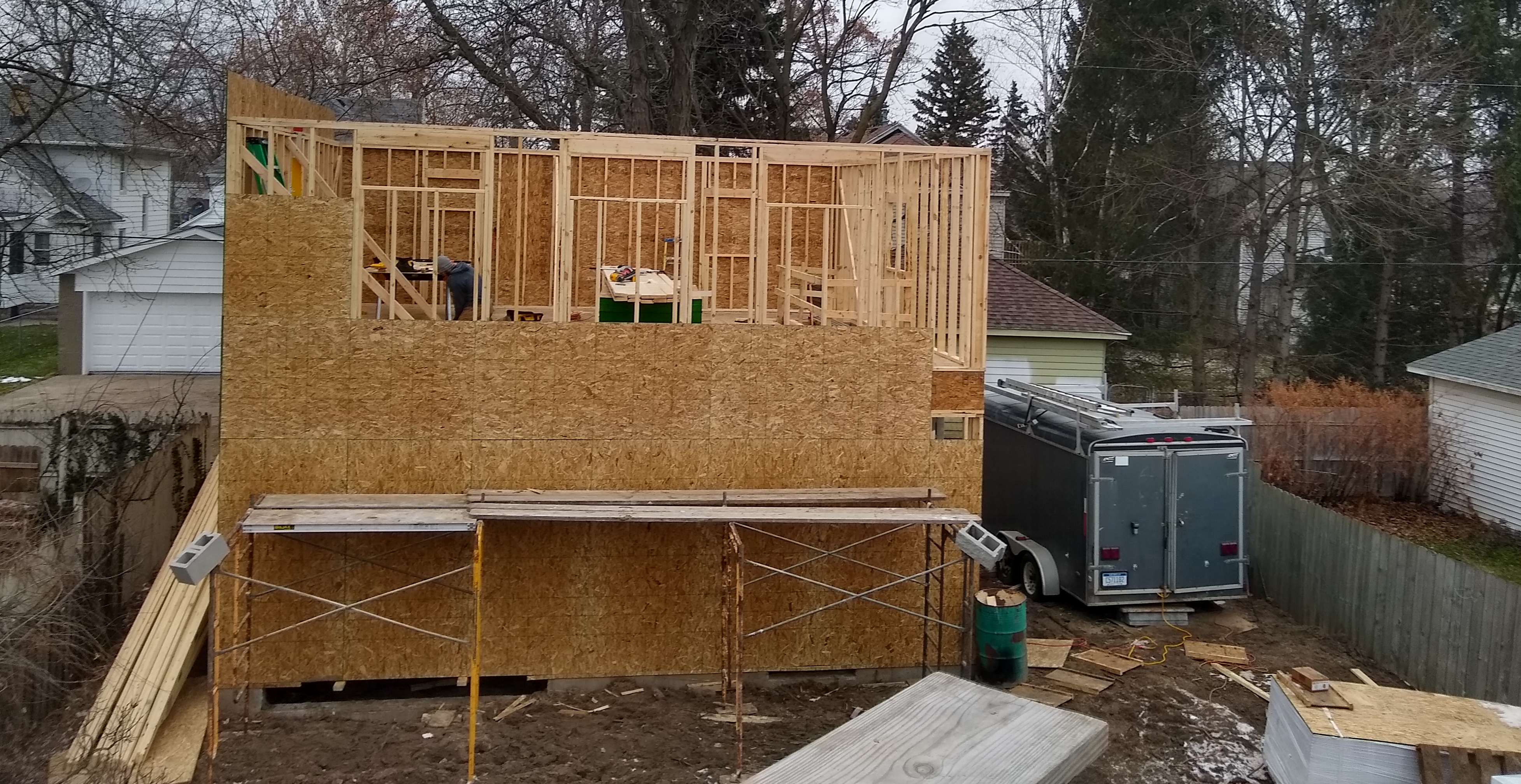

Going Up

Foundation: $21,885.00

After all of that it feels good to finally be above the ground, even if only by a few inches.

Construction proceeded rapidly once the project reached the framing stage; including the block wall.

The concept of massing is interesting. As the building goes up to two stories clad by bare materials it feels massive.

Then as windows and doors are installed, then siding added with all its horizontal lines, the feel of the building diminishes back down to that of the adjacent buildings.

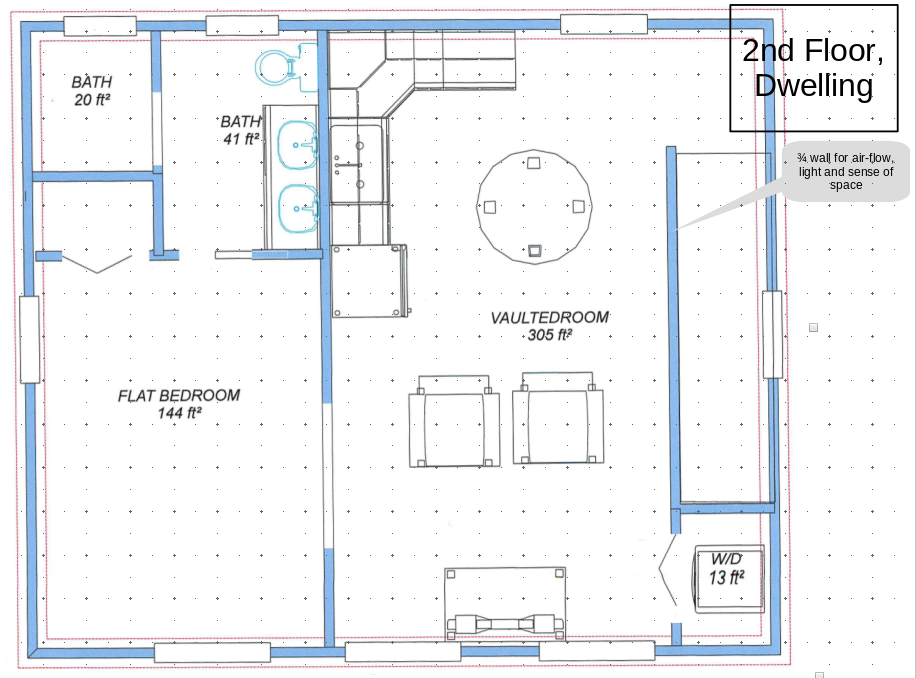

Indoors

The highlights of the interior design were generous closets [storage!], a large shower, and a vaulted ceiling in the living area.

Tips

- Keeping the ceiling as high as possible makes a space feel much larger. Higher ceilings also create potential storage.

- Especially in a smaller unit try to preserve corners and at least one wall. This maximizes the flexibility for furniture placement and art. In my traditional ~1,600sq/ft home, due to placement of the doors and windows there are very few walls; this is a frustration when trying to arrange a room. In the unit the use of transom windows left the entire south wall blank.

- If the intent is to rent the unit at market rate the bathroom is a big selling point. This is one category where new construction can have a big advantage over older construction.

- Storage, storage, storage.

Gotchas

The building code specifies a variety of minimum distances. These include distance of electrical service panel from a water source and the placement of vents. Contractors used to building or renovating large single family homes certainly know this but may neglect the detail, resulting in change orders which take time. Everything that takes more time finds a way of costing more money. In larger units this likely just isn't an issue that comes up very often - by virtue of size. Asking the [sub-]contractor about this may get grumbles, but you're paying him|her.

One criticism of ADUs is that the cost-per-square-foot is high. That is true. The cost of building does not scale on anything like a straight-line; there is a lot of stuff which is the same regardless of size. The amount of plumbing, venting, and wiring crammed into the walls of a small unit is remarkable. The principle cost savings with ADUs comes from the zero land cost.

And it is a more efficient use of public infrastructure to build additional units where it already exists [streets, sidewalks, water, sewer, etc...].

I would also argue that sq/ft is a generally poor measurement of livability. Design matters more than sq/ft beyond some low minimum. My traditional home at ~1,600sq/ft has a lot of not terribly useful space.

Pocket & Barn Doors

In a smaller space pocket and barn doors are a huge win. The bathroom door is a pocket door and the bedroom is separated from the living area by barn doors. These type of doors mean no space is consumed by the swing, preserving corners for furniture.

Flooring

Cost of flooring: $1,625

Easy to install laminate flooring is a great DIY project to save some money. Modern vinyl flooring provides a water resistant surface and with a little bit of thought can be run between rooms without seams – eliminating trip hazards. Getting the first few rows down straight involves some cussing, but then it really speeds up. Buy knee pads.

Laundry

Cost of Washer/Dryer: $1,240 Gas to laundry: $190 (unused)

Combination washer-dryers, with both functions in a single unit, help to save space. This all-electric unit also does not require a vent; it exhausts the heat from the dryer cycle using water, the same drain used for laundry. This saves energy on air-conditioning and heating.

The downside of the these combo units is that they take longer than traditional separate washer dryers. On the flip-side there is no need to move loads from the washer to the driver. Put the dirty clothes in the machine, set it to start at 3PM, then go to work and the load will be done when you return at the end of the day.

The laundry room also has a natural gas connection, just in case.

The extension of the vaulted ceiling from the main room into the closet allowed for an abundance of shelving.

Heating The Garage

Garage Furnace: $1,980

Heat was a big question. Different people could not agree on what would work well. There was concern about the residential space over the empty space of the garage. I had intended to heat the garage all along – making it far more useful – so it was really a question of how. In the end I went with the traditional gas “Hot Dawg” since several opinions were that electric would be too expensive to operate.

This is what required running natural gas from the house to the new building. As the gas was available I also had it run to both the laundry closet and the kitchen although it is used in neither.

Heating & Cooling The Apartment

The apartment’s HVAC is provided by a dual-head “mini-split” unit. The condenser is mounted on the exterior wall above the patio area. These units are very efficient for air-conditioning and extremely quiet in operation.

The apartment's water is heated with electricity, by a unit in the ground floor storage closet.

There are baseboard heaters in both the storage area and the bathroom. The heater in the storage area maintains a minimum temperature. There was a question if the air-flow within the unit would keep the bathroom warm enough which is why we installed an auxiliary heat source there, it has not yet been necessary to use it. Baseboard Heaters: $620 x 2

Kitchen

I was very fortunate. I was able to acquire from Urbaneer a show room unit they had in storage. Urbaneer products are designed for compact spacing. Finding small-format/urban appliances is a challenge, but the Urbaneer kitchen comes with all appliances – refrigerator, oven, dishwasher – integrated.

It is just a big piece of furniture that attaches to the plumbing. Getting it up a stairway - that's a challenge.

It’s a building!

Constant rain hindered the pouring of the walkway and parking pad but by spring it was finally a building. The dogs very much appreciated getting much of their yard back.

Finishing The Site

The Car Comes Home

On November 24th, 2019, 503 days after the project began the Model-T was finally brought to the garage for reassembly.

Total Costs

| Category | Subtotal | Category | Subtotal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excavation | $6,143 | Plumbing | $13,041 |

| Tree Removal | $3,665 | Electrical | $17,825 |

| Demo | $1,510 | Insulation | $9,165 |

| Water/Sewer | $20,920 | Drywall | $11,866 |

| Foundation | $21,885 | Bathroom | $3,510 |

| Block Wall | $1,430 | Garage Doors | $4,727 |

| Concrete | $4,965 | Kitchen | $1,395 |

| Framing | $28,661 | Finishing | $10,590 |

| Roofing | $3,565 | Flooring | $1,625 |

| Siding | $9,615 | Misc | $1,700 |

| HVAC | $15,444 | Paint | $1,251 |

| Total | $194,498 |

- Framing includes exterior windows and doors, excepting garage doors.

- Foundation includes concrete slab, drains, and everything under the building itself.

- Concrete is concrete work outside the building, including patio area (parking pad) and sidewalk.

- Excavation includes removal of debris.

- All categories include contractor management fees.

- HVAC includes both the apartment and the Hot Dawg in the garage; so the apartment by itself was ~$13,200.

- The cost of the stairway exists in both Framing and Finishing

Pemits & Fees

| Category | Subtotal |

|---|---|

| Mechanical (Gas Line) | $70 |

| Water/Sewer Connection | $960 |

| Water/Sewer Tap | $615 |

| Electrical | $277 |

| Mechanical | $165 |

| Plumbing | $140 |

| Building | $890 |

| Blower Door Test | $150 |

| Special Land Use | $2,015 |

| Total | $5,282 |

How Could it Be Cheaper?

There are a variety of things which could be modified in the design to reduce costs, which may or may not be appropriate for a particular use. Remember that an ADU has to fit some very site – and often family – specific requirements.

- If the garage or unit were more integrated.

- It may be possible to share a single HVAC solution.

- A single electric meter and panel, shared by the garage and the unit. This would save ~$1,500. Remember that the tenant of the unit must have access to their utilities. And do you want the potential for the unit to pay its own electric bill?

- Possibly fewer external doors.

- If your home is newer construction it may be possible to connect the structure to the home’s electrical service. With a 100 year old home that was a non-starter for me; it is guaranteed my home would fail a thorough electrical inspection.

- Use all-electric, which would remove the $2,390 in costs. The question is what the ongoing operational costs would be.

- Baseboard heaters in storage area and bathroom totaled $1,240. The unit in the bathroom appears to have been unnecessary.

- The block wall on the patio area was $1,580. This was a design choice, not a requirement.

- Do more work yourself to avoid contractor management fees. This is a perilous choice IMO, but might work for someone.

- Our design included a long access sidewalk at a cost of roughly $2,100.

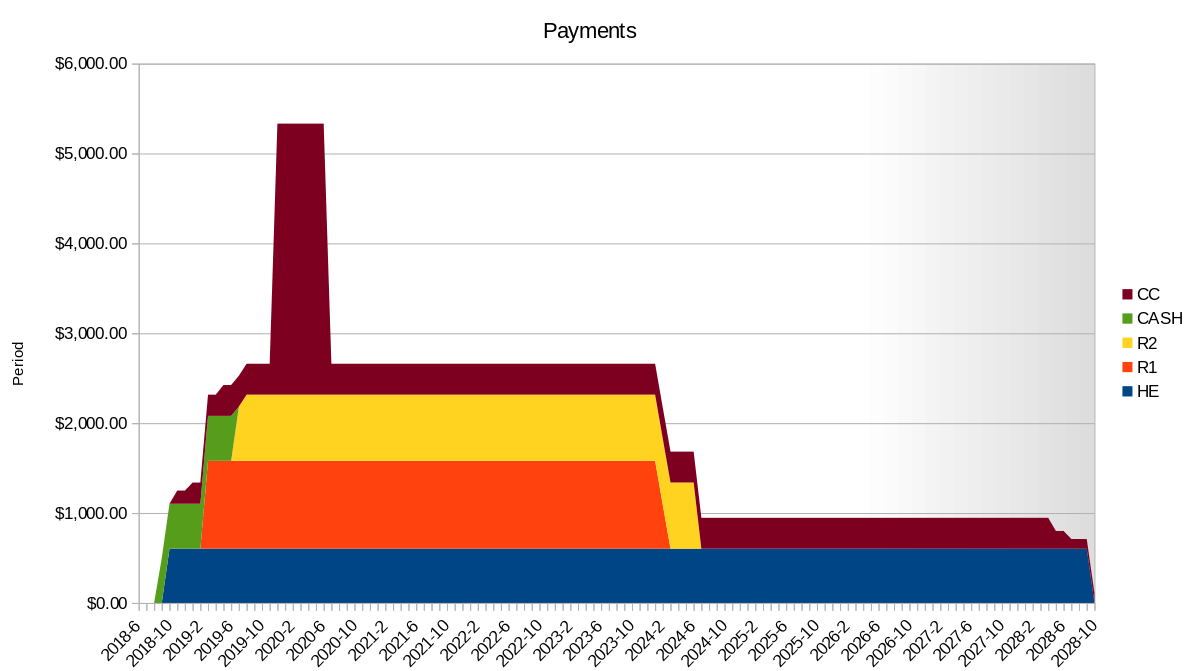

Financing

The financing of ADUs is a mess. Our project was financed in what is, sadly, the normal for ADUs: a combination of a Home Equity Loan (or HELOC), retirement savings, and credit cards.

The “Owner-Occupied” requirement present in the Zoning of ~3/4 of American cities renders traditional construction financing unavailable; these provisions render whatever value or revenue the unit would create as void in the eyes of the bank. Further financial skepticism is created by whatever Deed Restrictions may be required. As far as the bank is concerned you want to build something expensive and worthless.

The permit process also complicates financing: When do you acquire financing? Before you're approved, and then get denied; or wait until after you are approved? If you have anything like a timeline, such as a need for the unit, this is a major pain point. In the current market getting on a contractor's schedule, and thus his|her ability to schedule subcontractors, is critical. The longer a project takes to complete - guaranteed - the more it will cost you.

These zoning requirements prevent neighborhood level investment in housing.

If you intend to build an ADU begin banking both cash and credit immediately. A nimble dance of credit card balance transfers and payment programs is critical unless you have a large amount of equity. As mentioned previously the value of homes in Highland Park is comparatively low limiting how far home equity would get us.

Loans against retirement savings (401k), as R1 & R2 above, while tending to have aggressive repayment schedules, can typically be exercised in as little as 24-48 hours.

The total estimated repayment of the projects $194,498 cost should be about $237,490 over 10 years; the bulk of which will occur in the first five due to the terms of the retirement loans (R1 & R2).

As the intent of the dwelling unit is to ensure the availability of affordable housing @ ~$700/mo to family members the project will never generate actual revenue in those ten years. It may break even month-to-month at six years. However, the value of the unit should continue well past the ten year window.

Taxes

The tax code allows ~$5K in improvements or repairs to a rental unit to be deducted every year as a business expense.

As 75% of the cost is attributed to the dwelling unit ($145.5K) there is also depreciation of ~$5,300/yr.

Creating the unit did reduce our Michigan state "Homestead" tax exemption by 28%.

Ongoing Expenses

- Insurance on the rental unit is ~$30/month. $360/yr.

- Water/Sewer has been ~$30/quarter. $120/yr.

- Heating costs are impacted by weather, which has been very mild. So far the apparent cost of heating the garage (gas) is negligible.

Impact

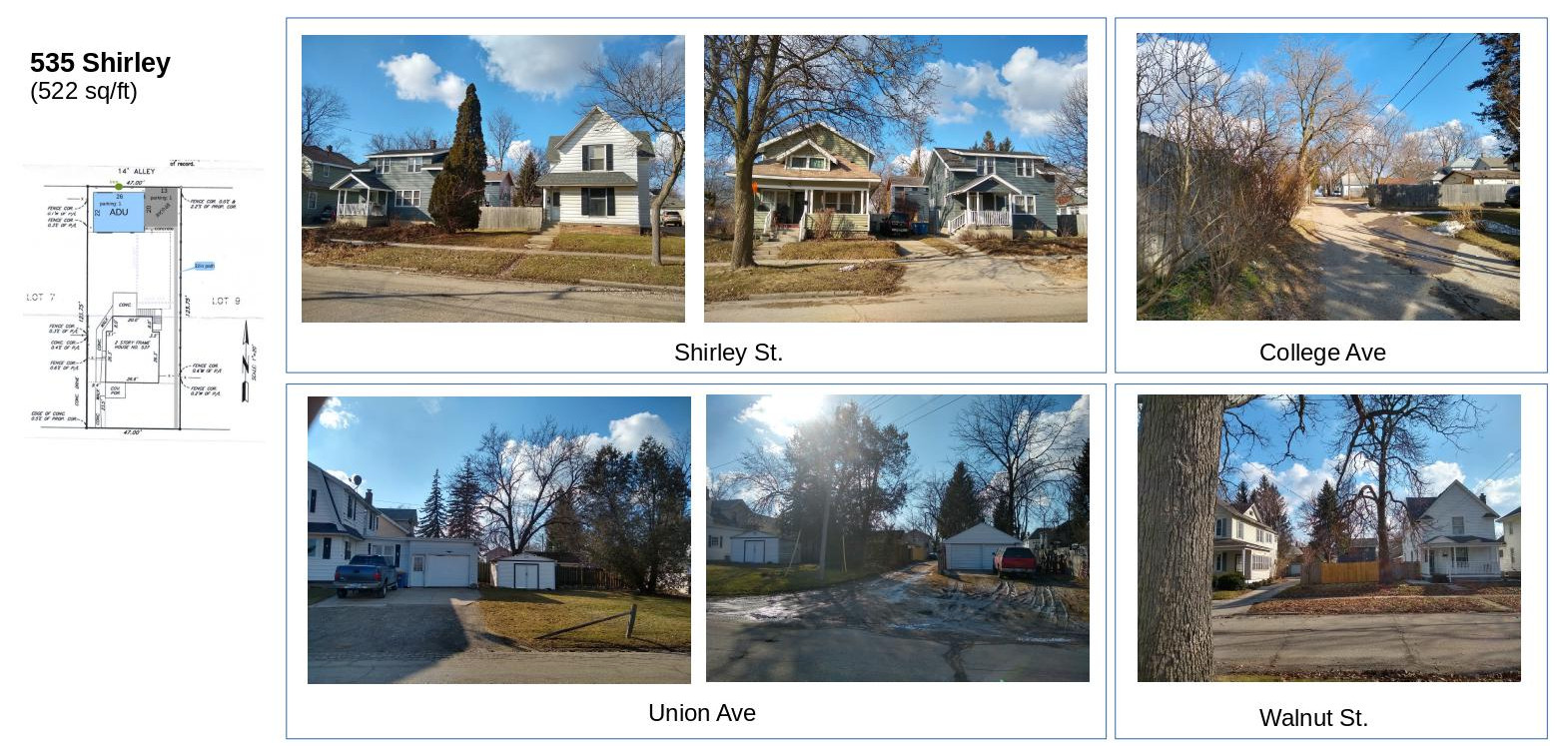

So what's the impact on "Neighborhood Character" of a two-story ADU? Here are is the building from every adjacent street, so you can determine for yourself.

Other

- There is a public Facebook album with more photos @ https://www.facebook.com/adam.t.williams.9/media_set?set=a.10216577844424264&type=3

- Financing and Property Tax Update (2025), UrbanGR 2025-08-28

Author: Adam Tauno Williams